Makers

Very little is known about the biographies of the makers or their artistic trajectories after their collaboration with European patrons ended. To our knowledge, all works were sent to Europe almost immediately after their creation, while their creators never set foot there. Displayed in galleries, museums, and at colonial and world fairs, the works were removed from their original context and imbued with new meanings shaped by colonial imagination and propaganda.

The iconography of the drawings recalls other art forms, including mural painting, sculpted ivory, and decorated gourds.

In this section, we aim to briefly introduce the makers and share the limited information we have about them.

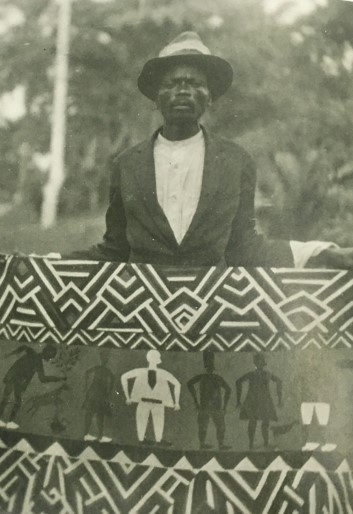

- Albert Lubaki (Mbanza-Ngungu, c.1896 - Kabinda, after 1939?)

Georges Thiry identified this man as Albert Lubaki. Photo from the Dierickx archives (RMCA).

There are very few sources available to verify the historicity of the figure of Albert Lubaki. The only known information comes from Georges Thiry, a territorial administrator who was the first and principal commissioner of Lubaki's watercolor paintings.

According to Thiry, Lubaki was born around 1896 in Thysville (today Mbanza-Ngungu) and was a Mukongo. He married into the family of the Songye chief Lumpungu — a woman named Antoinette. Based on signatures found on artworks in private collections and at the KBR, we refer to her as Mfumbi or Mfimbi, rather than Lubaki. In Kabinda, according to Thiry, Lubaki traded between the chief’s court and Elisabethville. He dealt in small objects and was also described as an ivory carver and mural painter. Thiry met Lubaki in March 1926, upon his arrival in the Belgian Congo, either in the cité indigène of Elisabethville or during the train journey there.

Based on letters from the Dierickx archives, Albert Lubaki was in Elisabethville in 1926 and the early part of 1927, after which records place him in Kabinda. He produced works for Georges Thiry between 1926 and 1932, for Gaston-Denys Périer in 1936 (through intermediaries in Congo such as Jeanne Maquet-Tombu), and for Eugène Pittard in 1939 (via Edmond Verhegge).

Lubaki — most likely alongside other makers such as Alphonse Kalenga, his wife (?) Antoinette Mfumbi, and Leonard Tshibambe — created drawings in exchange for monetary compensation. No works are known to have been produced after 1939, at which point the trace of Albert Lubaki is lost. No surviving works in other media (e.g., ivory) have been attributed to him.

In other collections, such as those of the KBR and Iwalewahaus in Bayreuth, we observe a variety of signatures, often appearing alongside that of Lubaki. In some cases, where additional signatures are absent, stylistic differences suggest that multiple makers were involved in producing the corpus. It remains unclear whether Lubaki acted as an intermediary between Thiry and other artists, or whether he worked independently, with signatures later attributed by Thiry or other patrons. What is certain is that the works attributed to Lubaki represent a collective body of work.

In contrast, the collection held at the RMCA presents a stylistically coherent group of works, bearing no other signatures. This consistency suggests that these pieces may have been created by a single hand.

- Tshela Tendu (Kananga c.1890 - Ibanshe, after 1953?), also known as Djilatendo

Tshela Tendu with his drawing. Photo from the Dierickx archives (RMCA).

There are very few sources available to verify the historicity of the figure of Tshela Tendu. The only biographical information we have comes from Georges Thiry, a territorial administrator who was the first and main commissioner of his watercolor paintings.

According to Thiry, Tshela tendu was of Luba origin and lived within the territory of the Kuba Kingdom. The two met in Ibanshe, not far from Mweka, in 1929, when Thiry was sent there for his second term in the colonial administration. Tshela tendu appears to have engaged in various forms of labor, including tailoring, mural painting, and hunting. After meeting Thiry, he also began producing drawings in exchange for monetary compensation.

After Georges Thiry left the Congo in 1932, no further works by Tshela Tendu are known. The last trace we have of him is a meeting described by Jan Vansina in 1953.

Tshela Tendu used multiple signatures in his works, here are some examples: Thelatendu; tshelatendu; Tshelatendu; Thelatedu; Tshiela tenda; Tshela tenduo; tshela tendu; Bidua tshela tendu; Tshela tenda; Tshelatendue; Tshalo Ntenduo; Djilatendo.

- Paul Mampinda (Sapo Buma, ?)

As he himself stated in the works, Mampinda was son of Mushiku, belonging to the Bena Kashiama tribe. We have no other information about this maker.

- Other works and makers

We invite you to take a look at the drawings stored at the Royal Library of Belgium:

Albert Lubaki: https://opac.kbr.be/LIBRARY/doc/AUTHORITY/14727372

Antoinette Mfumbi: https://opac.kbr.be/LIBRARY/doc/AUTHORITY/1452307

Alphonse Kalenga: https://opac.kbr.be/LIBRARY/doc/AUTHORITY/22193065

Léonard Tshibambe: https://opac.kbr.be/LIBRARY/doc/AUTHORITY/22193522

Tshela tendu: https://opac.kbr.be/LIBRARY/doc/AUTHORITY/14428184

René Masalai: https://opac.kbr.be/LIBRARY/doc/AUTHORITY/21366943

.JPG)